Introduction

As a final project for the agile hardware design class I’m taking this quarter, I’ve been making a sound chip. Currently, I just recently finished an implementation of a Game Boy audio processing unit (APU). (Later, I plan to add support for the NES APU.) Here are some gotchas I encountered while implementing a Game Boy APU.

NR31: All the bits

I had some confusion about the NR31 register (offset 0xff1b). The other NRx1 registers, which control length timers,

use bits 5–0 for the initial length timer, with bits 7–6 used for other purposes (NR11 and NR21) or left unused (NR41).

However, according to Pan Docs, NR31 uses all 8 bits for the initial

length timer. I assumed this was a mistake at first, given everything I

had read indicated that the initial length timer is set to 64 minus L, where L is the value in the register, which would

result in a nonpositive value for values that don’t fit in 6 bits. However, upon closer inspection of the relevant

GbdevWiki article, I noticed that for channel 3,

the minuend is actually 256, which would make subtracting 8-bit values feasible. I parameterized my length counter

module to add an override for the minuend in an attempt to fix the issue I was having with channel 3 (see the next

section), but the issue persisted.

NR30: Surprise, it exists

This is a simple one. When I implemented channel 3, I noticed that it was on constantly, even when it shouldn’t have

been, causing audio distortion. Turns out I never bothered to read about NR30 (offset 0xff1a). The only other used

NRx0 register, NR10, controls the channel 1 frequency sweep. NR20 and NR40 are entirely unused. I suppose I assumed that

NR30 was also unused. Turns out, NR30 does exist, and its single purpose is to turn channel 3 on and off. I added a

check for the relevant bit in my channel 3 code and the issue was resolved (which was the last issue I encountered—the

chip seems to work fine now!). Moral of the story: if you’re not going to read every single word of the docs, at least

give the register summary a thorough read.

Don’t omit a bit

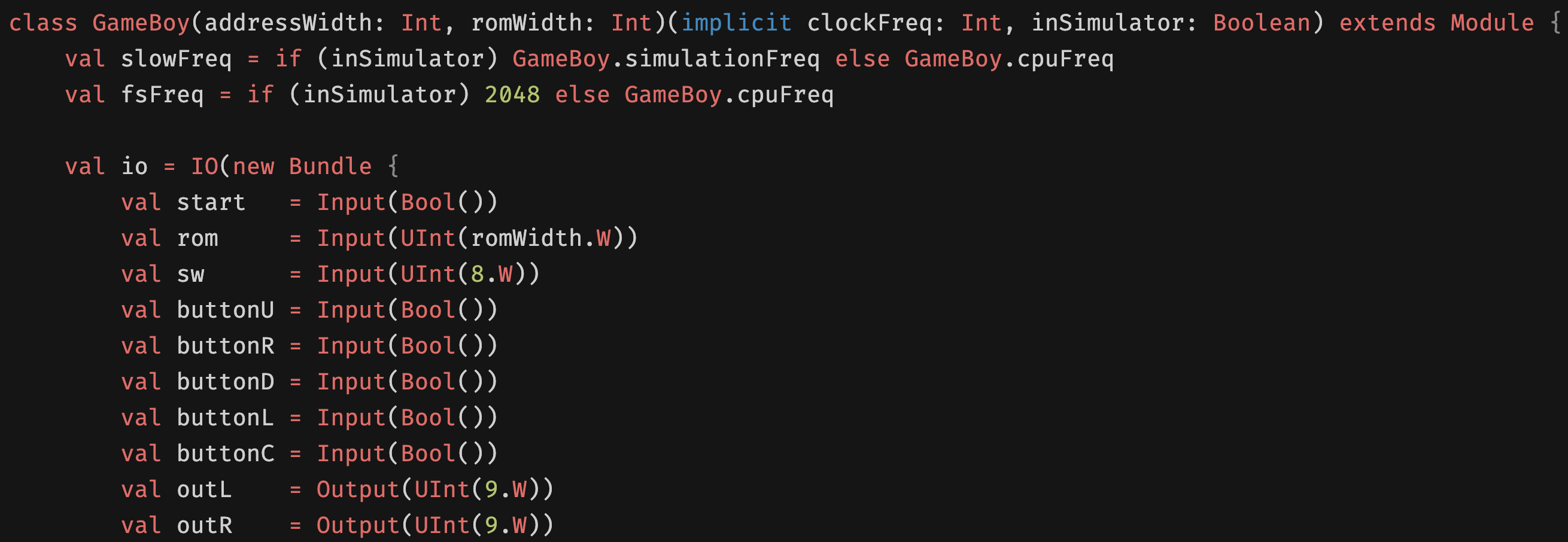

I updated my channel mixer to widen the output (9 bits instead of 8) but forgot to widen the Game Boy module’s output to match. Oops.

The division operator is not your friend

Using the / operator for division, especially if you’re using it with larger operands, can bring down your worst

negative slack significantly and cause timing failures. Solution:

SRT division. It takes (if I

recall correctly) a number of cycles equal to the bit width of the operands, but if you can’t get away with single-cycle

division, you have to settle. I ended up not even using the divider in the Game Boy APU implementation, but this is a

useful general lesson about division.

Maybe multiplication too

Avoid multiplication when you can. If you’re multiplying by a constant, perhaps see whether you can break the constant

into bits and taking the sum of the other operand shifted by the positions of every 1 in the binary representation of

the constant. For example, if you’re multiplying x by 18 (0b10010), try (x << 4.U) + (x << 1.U). If x is small

enough (3 or fewer bits in this example—1 more than the shortest stretch of zeros between ones), you can use bitwise OR

instead of addition for extra efficiency.

The ephemeral trigger

Music code will write 1s to the trigger bits of the four channels. It will not write 0s. To prevent eternal triggering, remember to turn the triggers back off after a cycle.

Instruction width woes

The instructions in the vgm format are variable width. The instructions you’ll find in a typical vgm file (namely, register writes, waiting and ending) are either one byte long (an opcode with no operands) or three bytes long (an opcode followed by two one-byte operands). If you want to make a state machine to execute these instructions, you’ll need to either read the instructions one byte per cycle (inefficient) or use a cache and read from the ROM in chunks as necessary (possibly more effort than one might bother to spare). There’s another approach, though: write a program in your favorite programming language (which ought to be something nice like C++, by the way) that reads in the vgm instructions and outputs a sequence of fixed-width instructions (in my case, three bytes) so you can just read from the ROM three bytes per cycle. No cache necessary, yet still one cycle per instruction. The downside is that you’ll need a larger ROM to hold the padding, but unless you’re using a BRAM-constrained FPGA or being greedy with how many songs you’re trying to fit in BRAM, you’re probably going to be fine.